By Dustin Slaughter

The Philadelphia Police Department and city solicitor Shelley Smith’s office are refusing to release documents pertaining to an intelligence-gathering program called “Look Up, Speak Up”. The Declaration filed a public records request in May with the intention of gaining a stronger understanding of Philadelphia’s version of The Nationwide Suspicious Activity Reporting Initiative (NSI), a jointly-administered Department of Justice/Information Sharing Environment counterterrorism program. The city has refused even an informal mediation session to settle this dispute. The Office of Open Records in Harrisburg will issue a final determination regarding The Declaration‘s appeal by August 7th.

“Look Up, Speak Up” was launched in January of this year and is geared specifically towards public transit riders, encompassing SEPTA and New Jersey’s PATCO system. The program was implemented through homeland security grant funding.

The Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR) program is facing heightened scrutiny and generating growing controversy from civil libertarians and some law enforcement officials for legally-problematic reporting standards and its questionable contributions to public safety. The collection, storage, and dissemination of so-called threat information, some of which is gathered and entered into federal databases, violates the Justice Department’s own regulations on criminal intelligence gathering.

Enacted in 1978, 28 C.F.R. Part 23 set a “reasonable suspicion” threshold that must be met by local, state, and federal law enforcement before information is entered into databases. Suspicious activity reporting more often than not fails to approach this burden.

Legal advocacy organizations such as the ACLU have started pushing back against the SAR program. The group filed a lawsuit in San Francisco on July 10th on behalf of five individuals to “challenge the legality of the federal government’s Suspicious Activity Reporting program,” per the organization’s press release. According to Linda Lye, a staff attorney with the ACLU of Northern California:

This domestic surveillance program wrongly targets First Amendment-protected activities, encourages racial and religious profiling, and violates federal law.

The five plaintiffs’ innocuous activities, ranging from waiting at a bus station to taking photographs, were reported to fusion centers and subsequently entered into a federal database.

One California man, an 87 year-old art photographer named James Prigoff, snapped photos of a “famous piece of public art called the ‘Rainbow Swash,’ painted on a natural gas storage tank” while vacationing in Boston. Law enforcement eventually tracked him back to his home in Sacramento via the license plate on his rental car. Federal agents then questioned him about his trip to Boston, and also approached one of Prigoff’s neighbors for questioning.

Another plaintiff, Tariq Razak, was reported for “surveying entry/exit points” inside a Santa Ana train depot while trying to locate an employment resource center, which happened to be at the same location. Razak, a U.S. citizen of Pakistani descent, was then observed leaving the depot with “a female wearing a white burka head dress.” The female was his mother, whom he was waiting for while she used a restroom. Law enforcement never visited Razak; his name was discovered after it appeared in SAR documents obtained through a public records request.

Entries made into federal databases, such as the FBI’s eGuardian, can remain stored for up to 30 years.

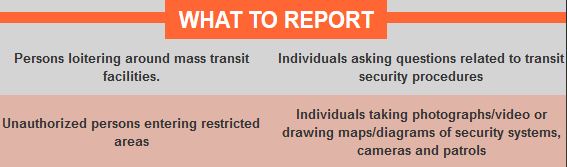

Authorities urge transit riders to report behavior listed above. Image: Look Up, Speak Up official website.

In addition to the racial and religious profiling and infringement of First Amendment-protected activity suspicious activity reporting at times creates, there is another troubling aspect: the value of the intelligence and the problems it creates for analysts tasked with sifting through reams of information pouring in from the public, patrol officers, fire department personnel, and private sector sources. A 2012 Homeland Security Institute study, Counterterrorism Intelligence: Fusion Center Perspectives, concluded that the SAR program “has flooded fusion centers, law enforcement, and other security entities with white noise.”

The report continues:

This white noise [created from suspicious activity reporting] complicates the intelligence process and distorts resource allocation and deployment decisions.

How “Look Up, Speak Up” works: transit riders place a call by dialing #1776 to report what they consider anything ranging from non-emergency nuisances to “suspicious activity”, although the website stresses that this number is not to be used for “immediate emergencies.” Callers are then connected to the city’s fusion center, the Delaware Valley Intelligence Center (DVIC). Based on the quality of intelligence, among other factors, an analyst will then disseminate information to local law enforcement personnel, and may also enter this information into an FBI database. Federal law enforcement may then choose to launch investigations into “strange” or “threatening” behavior, creating files on individuals and sometimes visiting homes.

When reached for comment about the program, SEPTA police chief Thomas J. Nestel III told The Declaration:

“I support and encourage any channel for the public to assist us in keeping the system safe.”

[…] from our journalism drones proving that the guard at the DVIC Fusion Center is an Eagles fan. Drone operator Mister […]

LikeLike

[…] anti-democratic affront to public school teachers yesterday, for instance, or how law enforcement may be abusing our privacy and civil liberties as we go about our daily […]

LikeLike