By Dustin Slaughter

“Spoils of War” is a three part series on PA law enforcement’s participation in the federal government’s asset forfeiture program. The Philadelphia Police Department is the first to be highlighted, and will be followed by State Police and Pennsylvania National Guard Counterdrug Program involvement.

Philadelphia Police Department participation in the Justice Department’s Equitable Sharing Program – also known as federal asset forfeiture – will continue largely without interruption, despite a widely-heralded recent order from Attorney General Eric Holder that limits what local law enforcement agencies can seize in forfeiture proceedings.

The Declaration has also learned that the program operates under very weak oversight from local and federal agencies, including the Office of Finance’s Budget and Program Evaluation section; the City Controller’s office, which serves as Philadelphia’s independent accounting agency; and the Justice Department’s Inspector General.

According to documents we obtained, dozens of discrimination lawsuits filed against the department – many likely settled out of court while others are still pending – have had seemingly no impact on PPD’s use of the program, despite a Civil Rights Act provision prohibiting agencies who violate Title VI from receiving federal funds. By settling out of court, in other words, the department has and will continue to exploit a legal loophole in order to keep awards flowing.

Tipped off by our investigation, the Controller’s office claims they will now begin auditing PPD’s participation in the federal program and will publish the findings as part of their annual oversight responsibilities.

An exhaustive Washington Post investigative series published last year revealed how the Justice Department’s Equitable Sharing (ES) program allows local, state, and federal police across the country to seize property, often leaving individuals, many of whom were not convicted or even charged, with little if any due process or legal recourse. The Post investigation also found almost no oversight of how police agencies were spending federal funds.

Philadelphia’s police department is no exception.

The series also detailed how the program, which was established in 1984 by the Comprehensive Crime Control Act as a tool to cripple large drug trafficking organizations as the Reagan administration’s so-called War on Drugs gained traction, has seemingly transformed into “a routine source of funding for law enforcement at every level.”

Critics of the program – including some Reagan-era officials – contend that the practice has become too widespread and abusive. Brad Cates, who once headed the DOJ’s forfeiture division, calls the program in its current state “a free-floating slush fund.” Asset forfeiture has more than doubled during the Obama administration.

How Holder’s Memo Will (and Won’t) Change Policing for Profit in Philly

Two types of operations comprise Equitable Sharing seizures: “Adoption” and “Joint”. Seizures stemming from what are known as “joint” local/federal investigations, which make up the vast majority of PPD investigations, according to documents, will not be impacted by Holder’s directive.

Due to an agreement between PPD and federal agencies, local police are permitted to continue splitting the proceeds from these joint investigations, an exemption cited in Holder’s directive (emphasis added):

“This order does not apply to 1) seizures by state and local authorities working together with federal authorities in a joint task force; 2) seizures by state and local authorities that are the result of joint federal and state investigations or that are coordinated with federal authorities as part of ongoing federal investigations…”

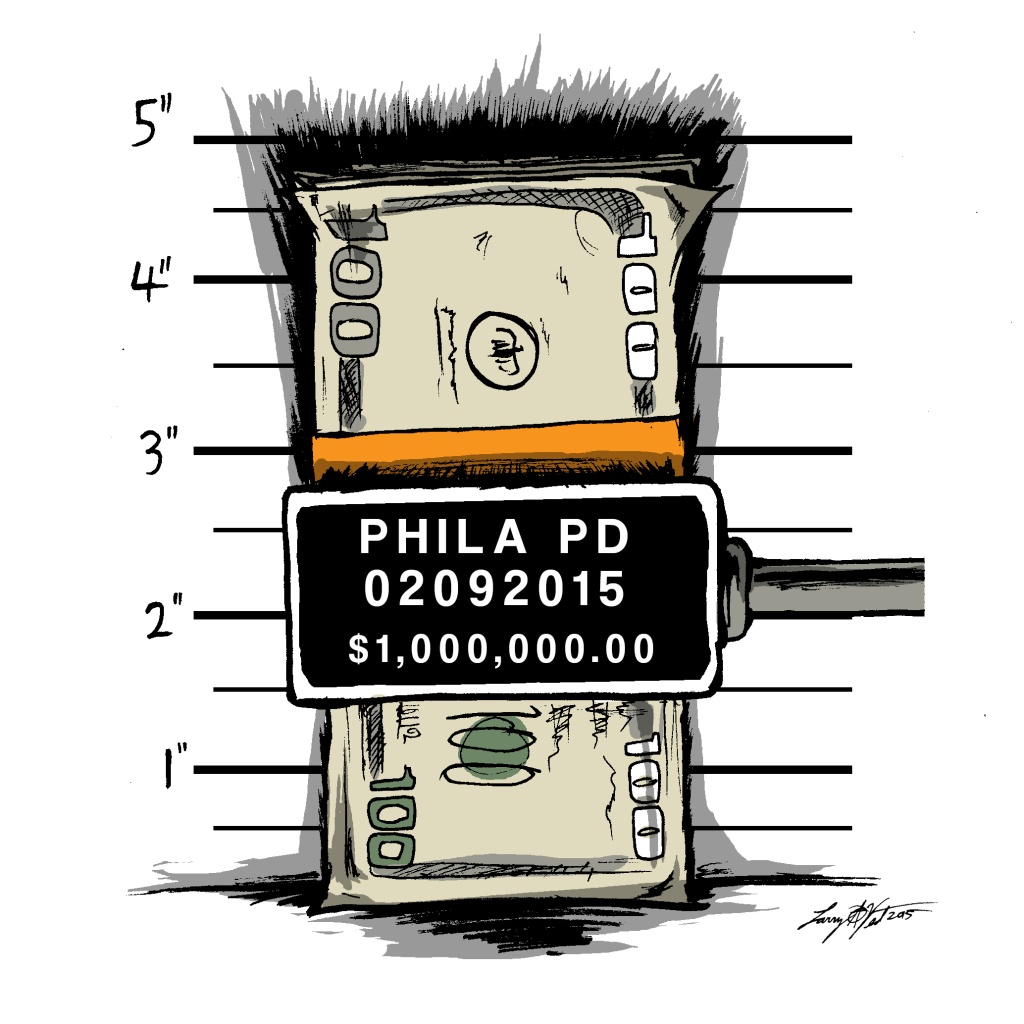

From FY 2010 to FY 2013, PPD contributed nearly 4,000 hours to joint investigations primarily with the Drug Enforcement Administration, but also with the FBI, U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Over that period alone the department added over $6.6 million from seized assets including cash, vehicles, money orders, bank accounts, and real estate.

Crucially, the documents also reveal that local police have concealed from the public how funds seized from joint investigations are actually spent.

In almost every “application for transfer” (known as a DAG-71 form) obtained by The Declaration, where officials are prompted to indicate how money will be allocated – in “Salaries”, “Purchase of Vehicles”, “Purchase of Equipment”, or “Other” sections on the form – the applicant checked off the “Other” box, and indicated: “This money will be used to help finance future investigations and other law enforcement needs as they occur” without further description or explanation.

One key factor in whether or not local police can successfully adopt their share of seized assets will likely remain shrouded in secrecy, too, as part of the application describing what constitutes “unique or indispensable assistance” to joint operations is redacted.

The order allows for the seizure of items deemed a direct threat to public safety, including “firearms, ammunition, explosives, and property associated with child pornography.”

Holder’s directive will have no impact on state and local civil asset forfeiture (a practice facing increasing pressure from a growing coalition calling for reform in Pennsylvania) such as that of the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office, as detailed in a series of reports by investigative journalist Isaiah Thompson.

In addition to these joint operations with federal agencies, the Philadelphia Police Department co-hosted an “interdiction” seminar last year with a controversial private firm called Desert Snow. According to a brochure obtained by The Declaration, Desert Snow teaches police officers how to successfully locate and seize cash during traffic and pedestrian stops. Desert Snow also operates a private intelligence network and online social hub for “highway interdictors” called Black Asphalt, that contains “tens of thousands of reports about American motorists, many of whom had not been charged with any crimes,” according to The Washington Post. These reports contain “law enforcement sensitive information about traffic stops and seizures, along with hunches and personal data about drivers, including Social Security numbers and identifying tattoos.”

Local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies can access this members-only database at will.

Weak to Nonexistent Oversight

“The City accounts separately for federal equitable sharing funds received from DOJ and from Department of Treasury, local, and state. I would not describe that as ‘oversight.’ It is what the agreement specifies.”

– Mark McDonald, Nutter’s press secretary, in an email to The Declaration

The agreement McDonald referred to is found in the Justice Department’s Equitable Sharing Guide, a set of rules for the ‘Governing Body Head’ – in Philly’s case, the Office of Finance’s Budget and Program Evaluation section, currently headed by Rebecca Rhynhart – which is designed to ensure Justice funds are not commingled with state and local asset forfeiture awards.

That is where any semblance of police department Equitable Sharing participation oversight ends, as there does not appear to be any independent agency monitoring of how local police actually spend these federal awards.

Rhynhart, currently tasked with approving ES certifications along with Commissioner Charles H. Ramsey, co-signs affidavits attesting to the veracity and accuracy of these certifications the police department submits to the Justice Department. Curiously, one such affidavit from 2012 lacked her signature:

A certification for the following fiscal year – the same year another anomaly I’ll touch on in a moment appeared – seems to include Rhynhart’s signature, but her name and title have inexplicably been redacted:

Those items may be perfectly innocuous, but because these certifications are effectively sworn statements, we believe they deserve scrutiny.

A city official familiar with the process says Finance officials did not audit police expenditures because they do not consider Equitable Sharing awards to be federal grant money (which Finance audits expenditures of annually), but instead as “revenue sharing”.

Rhynhart did not provide comment for this story, but instead referred questions about what oversight role her office plays to the Mayor’s spokesperson, Mark McDonald, whose statement is included above.

The documents released by the city also reveal that starting in fiscal year 2013, City Controller Alan Butkovitz, who serves as the city’s fiscal watchdog, was inexplicably listed as an “Independent Accountant”.

When reached by phone, Controller spokesperson Brian Dries could not explain why the DOJ decided to add the “Independent Accountant” section, nor why Butkovitz’s email address was included by the police department. PPD did not respond to questions and requests for comment on any aspect of this story.

As a result of inquiries by The Declaration, Dries says the Controller’s office investigated police participation in the program for fiscal year 2013, and found no improprieties or discrepancies.

A Justice Department official, speaking on condition of anonymity, indicated the agency has never audited the police department on Equitable Sharing matters.

The DOJ Inspector General performed an audit of the District Attorney’s Office’s use of the federal program from 2003 to 2006, however. Over this three-year period, IG found inaccurate certification reports and a failure to “establish a segregated bank account” for its ES proceeds, among other problems. DOJ Inspector General audits are triggered by a whistleblower allegation; a request from a member of Congress; or of the IG’s own volition.

Check out all Equitable Sharing documents released by Philly Police for FY 2010-2013 here.

Larry West, a Philadelphia-based graphic designer, graciously contributed artwork for this story. More of his work can be found on his website.

For more stories like this, subscribe to The Declaration for email updates and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Reblogged this on Joshua Scott Albert.

LikeLike

I’m proud of McDonald for his willingness to comment on this story. I hope he’ll continue to kindle this newfound friendliness of his toward reporters.

LikeLike